Data on incinerators in the Tokorozawa area

@ There are 64 licensed industrial waste

incinerators operating in the Tokorozawa area. Of the 64 incinerators,

51 have capacities below 5 tons per day. Until a 1997 amendment

to the Waste Management Regulations, incinerators with capacities

below than 5 tons per day remained outside the regulations.

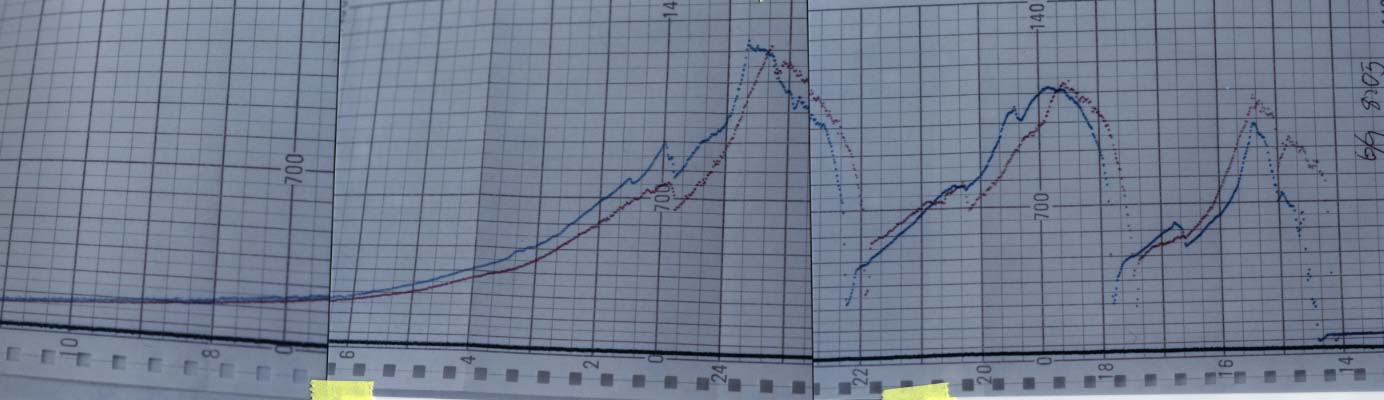

In the graph below, we can see the results of Saitama PrefectureÕs

environmental policy. The authorities repeatedly encouraged notorious

open-burning violators to erect incinerators with capacities below

5 tons per day, which at that time were unregulated by law.

@Due to two amendments in Saitama prefectureÕs

waste management regulations enacted in 1997 and 1998, which strengthened

regulations in incinerator construction specifications and operation

maintenance, many incinerators have shut down operations, either

temporarily or permanently. Citizens were led to believe that

environmental conditions would improve. Yet residents living near

incinerators, oppressed by smoke, have found the incidence of

pollution to be more serious than ever.

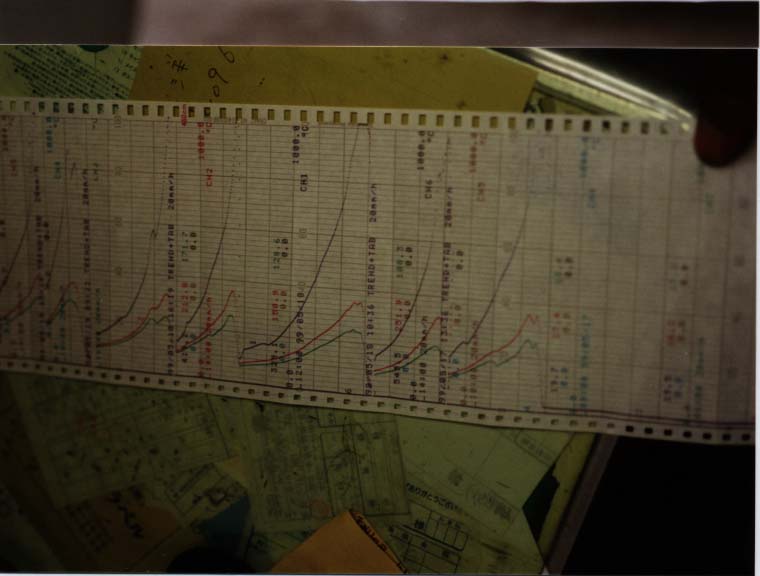

Presented below are analyses results of data compiled from incinerator

permit applications on file at the prefecture, and from data culled

from incinerator logbooks during citizen inspections.

PC. Examining temporary and permanent shutdowns, and upgrades

in incinerator capacity.

Operational status of incinerators in the Tokorozawa area (by

number of incinerator)

@ Saitama Prefecture reports that out of the 64 licensed industrial waste incinerators in the Tokorozawa area, 16 have shut down permanently, 10 have shutdown temporarily, one is being rebuilt, and 37 are operating as usual. Citizens report that 3 out of the 10 temporary shutdowns have no apparent plans to resume operations. The plans of the remaining 7 facilities are unknown.

@From the above graph, we can see that

even though 16 permanent shutdowns have been reported, as the

incinerators were the smaller type, overall there has only been

an 8% reduction in the total amount of wastes incinerated.

@From the permit applications filed with

the prefecture, we can see that during the 1990Õs there was a

drastic increase in the overall amount of incineration. In 1997,

the 64 industrial waste incinerators collectively burned an average

of 407 tons per day. Between 1997 and 1999, there were 16 permanent

shutdowns, with a collective decrease in incineration of about

35 tons per day. But in 1998, which falls in the same period,

an existing facility, Yamaichi Shoji, was granted a permit to

rebuild, increasing the facilityÕs capacity by 20 tons per day.

So the actual net decrease in total wastes burned works out to

be around 15 tons per day.

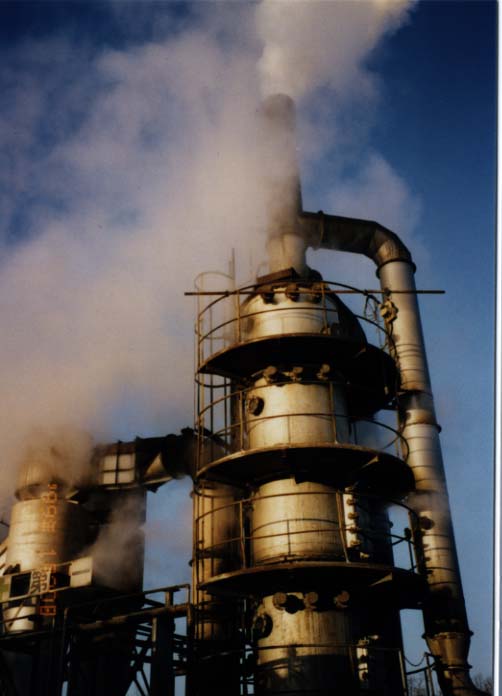

QCAbout industrial waste incinerator operating conditions

Standards for incineration design and operations were strengthened

in December 1998. In April 1999, waste storage regulations were

also strengthened. Yet recently the smoke has returned to wreath

the Kunugiyama area, expecially in the early morning hours. Behind

the seeming optimism of strengthened regulations lies the darker

reality of night burning, incinerators operating with hatches

open, and refuse dumped into the hatch while the incinerator is

in operation. Poor operational procedures such as these are responsible

for airborne ash, black smoke, and chloride smells. And still

nothing has been done about the oversized heaps of refuse, which

are now flagrantly in violation of waste storage regulations.

PjComplete incineration and temperature

control

Nearly all of the incinerators in the Tokorozawa area are

batch-mode types designed to operate for 8 hours per day. Only

one facility, which operates two furnaces, is equipped for continuous-

mode incineration. None of the incinerators is equipped with a

grate to agitate or mix the refuse to ensure even burning. Complete

burning is impossible to attain under these circumstances, and

during the daily start-ups and shutdowns, large amounts of dioxins

may be produced. In order to attain complete combustion, the prefecture

advises: ŅFill the furnace with the appropriate amount of refuse

once per day. Use the auxiliary burner to assist combustion. Do

not open the hatch until the furnace has achieved complete burnout.

If the temperature in the furnace drops below 800, use the auxiliary

burner to raise the temperature. Toward the end of incineration

use the auxiliary burner once again to insure complete burnout.Ó

However, because there are so many incinerators in this area,

the ŅadviceÓ and ŅoverseeingÓ capabilities of the prefecture authorities

are in question. The incinerators, unequipped with agitator grates,

cannot possibly burn waste effectively. On inspection of the ash,

partially burned lumps of matter are clearly visible to the eye,

and the amount of partially burned matter exceeds the 10% limit

imposed by waste management regulations. The authorities show

no signs of acting on this violation.

P24. What the temperature

logs reveal about operating conditions

The recent amendment to the waste management regulations allows

citizens to inspect maintenance logs kept by industrial waste

incineration facilities. On inspection, temperature measurement

logs revealed that it was common practice for operators the open

the hatch while the furnace was in the middle of the burning process.

The logs also revealed that operators fed the furnaces several

times per day, did not ensure complete burnout, and did not comply

with registered operating hours. Some operators had even turned

off the devices to measure temperature during operations. The

waste management regulations were strengthened over a half a year

ago. What are the authorities doing?

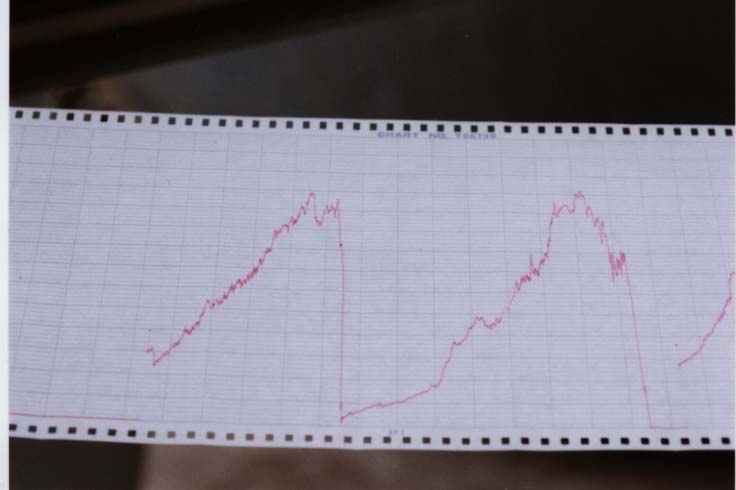

Temperature measurement graphs show a pattern which concurs

with feeding the furnace in the middle of a burn cycle. This pattern

repeats two or three times per day. It is also obvious that steady

temperatures of at least 800 are not being maintained. The graph

on the right is from a facility that admits turning off the recording

device as soon as the temperature reaches 800.

The condition of incinerator ash (incomplete burning)

From the looks of the partially burned objects in the ash,

it is obvious that burning is incomplete. Not one of the facilities

in the area has a roof over the ash storage receptacles, which

leaves the ash open to the effects of rain and wind. We remain

apprehensive about seepage and windborne spread of dangerous substances.

28. Citizens witness smoke black with fly ash belching from the smokestacks. Black smoke is emitted in the mornings and evenings during start-ups and shutdowns, and during operations when the hatch is opened to feed the furnace.

In August 1998, this incineratorÕs hydrogen chloride emissions were measured at 6100ppm (the regulatory guidelines set the limit for HC emissions at 700ppm). Because the test was voluntary, the prefecture says they have not offered any guidance on this matter. Citizens visiting the facility report chloride smells in the vicinity.

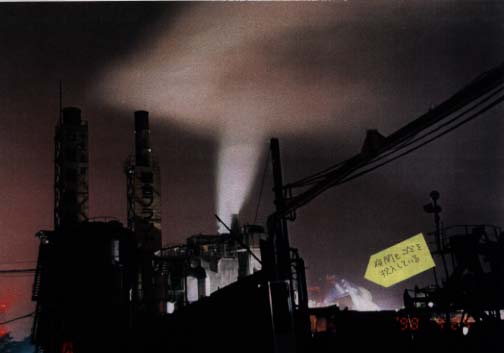

S@ Night operations

After citizens and authorities have gone to sleep, the facilities

can operate as they please. In the mornings the area is wreathed

with smoke. Operational hours written on the incinerator permits

are flagrantly ignored.